Infographic: Catching online scammers

The infographic I designed below is quite large (1200×7700 pixels), so I’ve split it into content sections so it won’t completely clog pageload times. Each of the content section images is “Lightboxed” – meaning that if you click/tap on them, they will expand to fill the screen.

How to download the full-length version of this infographic

If you want to download the entire infographic, click on this link and then right-click (CMD+click on a Mac) and select “Download.” If you use it or share it, please credit me and/or link back to this site & post. Also, a little love for the brilliant Dmitri Williams and Ninja Metrics would be in order as well.

Sign up to get an email when Dave LaFontaine's "Google Analytics Cheat Sheet for Creative Professionals" comes out.

How tracking shady orcs and stolen magic swords in online games helps catch con men, hackers, and e-commerce scam artists

“Remove 99% of the hay, and call in a human to locate the needle.”

(This story originally appeared as part of an examination by AIM Group into the efforts to crack down on online scammers and hackers that infest e-commerce sites.)

In folklore and legend, mythical characters like leprechauns tricked humans by selling them gold coins that turned into turnips when exposed to sunlight. That behavior continues in Massively Multi-Player Online Role-Playing Games (MMPORGs) like World of Warcraft, Everquest or EVE, where players trade spells, weapons or merchandise for real money – often encountering the same scams, money-laundering and con artists as in the real world.

But now “big data” analysis of these fantasy world crimes is helping operators of online marketplaces identify and catch real-world criminals.

“This all started when I bought a laptop off of Craigslist,” says Joshua Clark, Ph.D. student and researcher at USC-Annenberg. “It was a dud, just didn’t work. And when I went looking for the guy who sold it to me, of course he was long gone. So rather than just sit and be angry, I decided to see if there was something that I could do about it, using my data analysis skills.

“Now, I can’t survey everyone on Craigslist and ask them the question, ‘Are you trying to rip someone off today?’ But within a game, we have a data-rich environment which means I can track people who are scamming and ripping people off.”

It turns out that human behaviors are much the same whether in the real world, an online fantasy game marketplace, or classified advertising listings. Human beings interact, test the boundaries of behavior, share knowledge of good deals, and – unfortunately – victimize each other online, in the same ways as they do offline.

Because game players are willing to part with real money in exchange for things that allow them to win (or beat up on other players) in that game, complex online marketplaces have sprung up where wizards, elves, or space aliens sell magic swords or spaceships to players who don’t want to go through all the in-game “work” to earn them. Those real-money transactions sometimes lead to fraud or abuse.

“Because of the fact that you can buy and sell virtual ‘goods’ on MMPORGs [such as “World of Warcraft”], they are, in fact, quite similar to online classified websites such as EBay,” Gyutae Park, cofounder and game theory expert at MoneyCrashers.com, told the AIM Group. “Therefore, one opens themselves up to the same risks and dangers where criminals spot and take advantage of holes in the networks.”

A key advantage for investigators? The technological framework of online games records everything players do.

And it turns out that the behavior of these virtual criminals reveals patterns that can then be applied to other settings.

“I tell clients that it’s like their game marketplaces are giant bazaars, with people running around in them, buying, selling, talking to each other,” Dmitri Williams, CEO of Ninja Metrics, told the AIM Group. Ninja Metrics has a virtual team of researchers based in Los Angeles, Minneapolis and Northern California. “On ground level, all you see are the people and what they do in the moment. But with data analysis, it’s like you’re floating above them, able to see everything they do, everything they buy, everything they say.

“There’s always been this gap between what people say they do, and what they actually do. But in these virtual online games, you have perfect unobtrusive data where the players don’t even know you’re there with your white lab coat and your clipboard.

“In the online game world, [as a researcher, you have powers of insight like] God. You know everything about everybody without having to ask. Because you have created this world, you own this world, and you control everything in it.”

Once data analysts gather a large sample of data about transactions, interactions and results of player behavior in a game, they can build models and predictive engines based on the trends.

One of the gaming environments that researchers have looked at is Steam.com, where there is a robust online marketplace – it’s a total virtual economy. “You can trade a hat for another hat. Or weapons, or whatever,” says Clark. “The problem is that nobody knows what anything is really worth, so people get scammed all the time.

“Someone tells you that ‘My special hat is worth $100 on EBay.’ So you make the trade, and then find out that the going price for the item you really got is only five cents. In this situation, we have a place where people are taking advantage of each other, and almost everything they do is recorded by the game.”

Online connections reveal crooked intent

One key researchers have discovered is that it is not necessarily the behavior of suspects that red-flags them. Instead, it is their connections and their interactions with others. To make a real-world analogy, it’s like police paying special attention to “known associates” of a crook they catch. If you have a guy in custody, and all his friends are street-level drug dealers, it stands to reason that you have a street-level drug dealer. But if his friends are international bankers, arms dealers, private jet manufacturers – well, then you’re more likely to have a drug kingpin in custody.

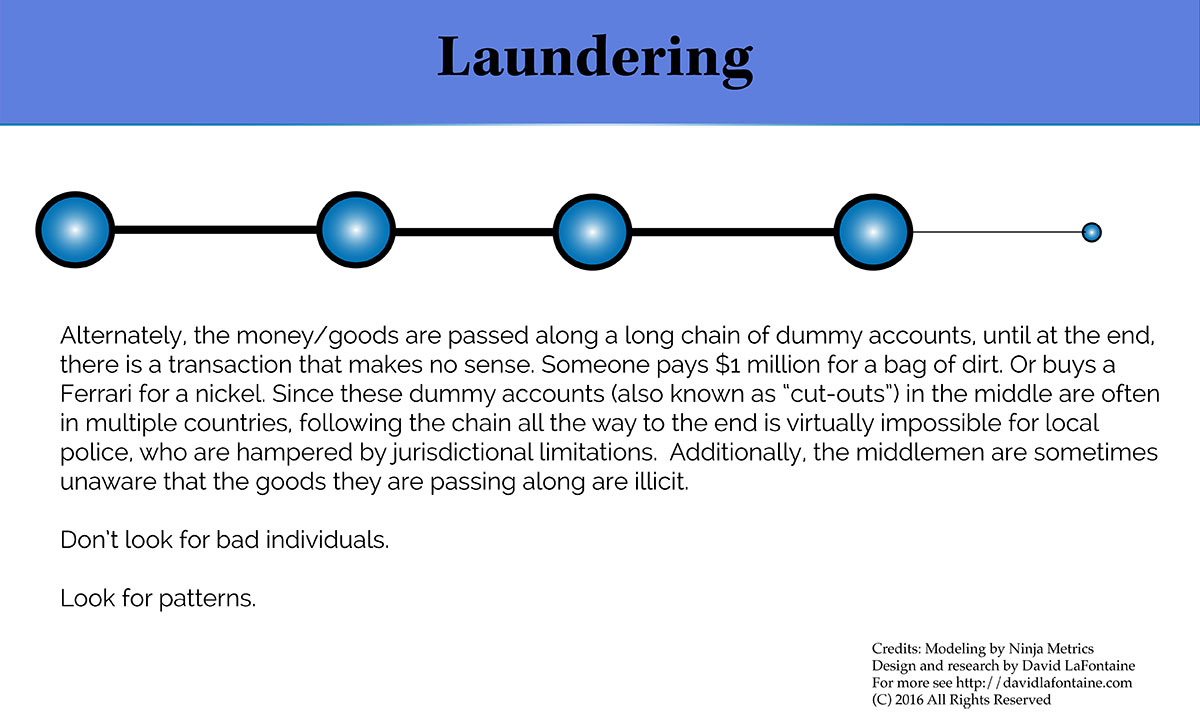

Researchers look for unlikely chains of interaction – such as a person taking $100,000 (in virtual or real currency), using that money to trade for something, with trades from person to person until you get to the last person in the chain – who gives that $100,000 away for almost nothing. From a limited perspective, you might see a guy who just paid $100,000 for a pack of chewing gum. Strange, but maybe this guy really likes gum.

But from a game overlord position, you have spotted this chain of transactions that ended with a crazy, illogical interaction. So now you know to look at everybody along this entire chain with extra scrutiny.

“Catching criminals in any system is a combination of tracking their behaviors and their social networks, and then creating predictive models,” Williams said. “With the right input and set up, anything can be modeled out.”

A big part of the work of applying these mathematical models to catch real-world criminal on EBay, Kijiji or Craigslist lies in the hard computing power needed to run complex mathematical models on mountains of data. Clark laughingly described how the sheer volume of numbers he was crunching overheated his desktop computer, requiring him to install special fans to cool the motherboard and keep it from melting.

The computer power is needed to construct what is basically an Artificial Intelligence that can sort through billions of data points and trillions of possible combinations of connections.

“The first thing you have to do is identify who are the scammers,” says Clark. “Now, in the real world I can’t go in and ask somebody directly if they are a criminal or know somebody who is shady.

“But in the online gaming world, the players got so tired of being ripped off, they built a site to report this. So if someone has traded you a hat that is worthless, and you can provide proof and evidence, then they add that to a database of dishonest brokers within the game. And that person has a little flag beside their name.

“I was able to use that to construct a training data set.”

Williams, Clark and other data wizards use an interesting methodology to refine their criminal-finding robot – they split the data from games into two parts. Already knowing who the crooks are, they then use the Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis, a program that looks for correlations between known bad actors, such as:

- Do the scammers all have specific patterns of friendships?

- Are they online during particular hours, and for particular durations?

- Do they all follow the same pattern of who they connect with?

- Do they send the same number of messages back and forth before they backstab someone who trusts them?

- Does the message content contain similar phrases (such as “Nigerian Prince”)?

Once the artificial intelligence has found what it thinks are reliable correlations between scammers, the researchers then feed the fraud-finding engine the other half of the data, to see if it highlights the people in that half whom they already know to be dishonest.

“Our model has demonstrated that it has a statistically significant boost in power to detecting fraud,” Clark said. “It’s not an indictment. But it’s a way to highlight people who may pose a risk.”

This is the same kind of data analysis that law enforcement agencies use to track money-laundering and criminal activities with drug cartels.

“There’s a data set that goes under the acronym CAVIAR – I don’t know if it’s publicly available, but it’s available to researchers,” said Williams. “CAVIAR looks at criminal organizations, drug cartels specifically, and who is connected to whom within them. It’s a tool for social network analysts to look at to see what makes these groups tick.”

In more basic terms, teams use a digital dashboard of data analysis that shows all kinds of views of the large and complex trends in an online economy in real time. In this case, it is showing a prediction of “churn,” or leaving the game.

Williams’s company calls it a Katana Social Analytics Engine.

“The Katana Engine takes data from systems via an API, runs them through our algorithms, and generates predictions about what individuals are likely to do,” he said. “We report those, how important they are, and how certain we are of our results [based on regular checks]. Our dashboards lay this out, and in this example we are showing a prediction around quitting [churn].”

Williams confirmed Ninja Metrics is actively working with e-commerce companies to catch fraud, but he declined to provide specifics.

Of course, sometimes crimes in virtual worlds, whether MMPORGs or e-commerce or classifieds, bleed over and have effects in the real world.

Steal an imaginary magic sword – get knifed in the real world

Game players have murdered each other in the real world over magic swords or potions that were stolen in the game. Criminal gangs in Asia have kidnapped or threatened game developers, to get their hands on special weapons that they can then use in the game, to defeat rival gangs in the game universe. And it’s common knowledge that in developing countries like China and India, teams of children play online computer games, racking up experience points, earning virtual gold or objects, which are then auctioned off on EBay, Craigslist or other online marketplaces.

“In 2011, North Korean hackers managed to gain access to two of South Korea’s most popular MMPORGs,” says Park, whose MoneyCrashers.com is based in New Jersey. “They then auto-played the games for hours, collecting large sums of virtual gold, which they eventually sold through auction websites. The money was then allegedly used to fund the country’s nuclear weapons program.

“Mobsters from Russia and Latin American drug cartels are also now involved in laundering money through MMPORGs, such as World of Warcraft. They buy virtual gold with dirty money and transfer it to a player in another country, who then converts the gold into cash. One of the most popular MMPORG scams involved the game EVE Online, where criminals set up a Ponzi scheme and conned users out of more than $50,000.”

According to game theory and Big Data researchers, what they call “behavior mapping” is crucial to being able to use the mathematical models from online games to catch real-world scammers. That means that the system of incentives, rewards and risks matches up from one platform to the other.

People in online games tend to act the same with their virtual money as they do with real-world money. They indulge in splurge shopping sprees or hoard coins in the same patterns in response to stimuli as they do in the real world. However, researchers point out that we are a lot less sensitive to certain risks in the online world – players tend to be a lot more cavalier about getting shot or stabbed in fantasy worlds than they do walking down a dark alley, for example.

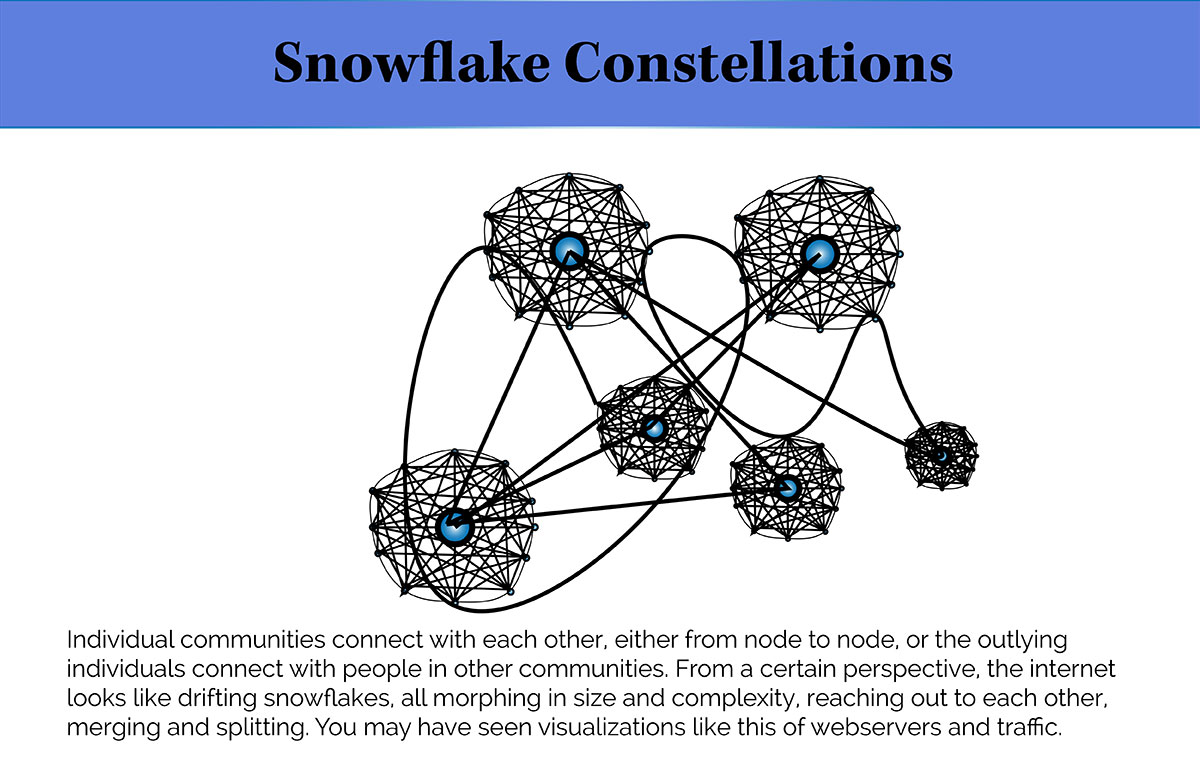

This is why game data analysts look at connections between players: Graphing them into shapes shows patterns, and those patterns can then be matched from the virtual worlds to the real. One person is a point, two people connected is a line, and three people connected looks like a triangle.

“You can locate the ‘shapes’ in the interactions of users and events in a graph, a collection of nodes connected by weighted links,” says Park.

By tracking the way crooks in these virtual games interact, researchers can then look for similar patterns in online marketplaces.

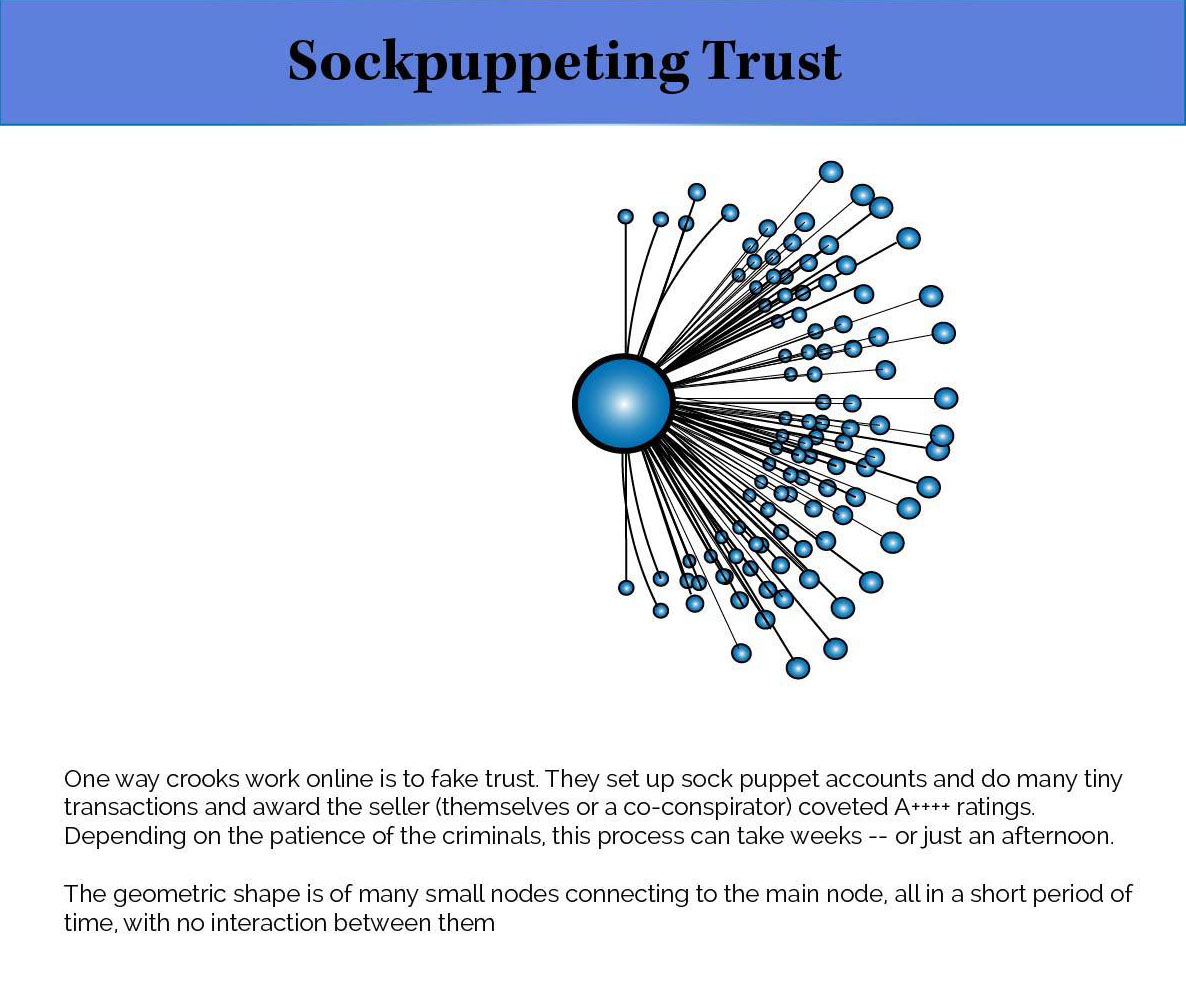

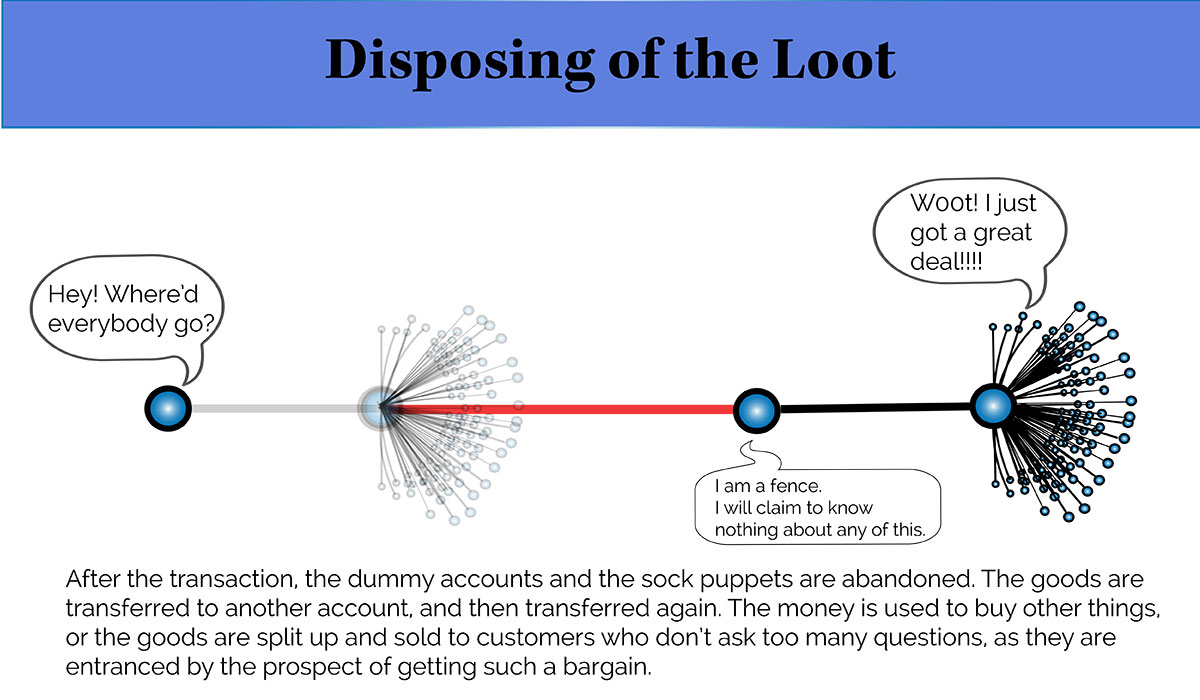

For example, one of the best ways to exploit a financial ecosystem is to gain trusted status and then betray that trust. That phenomenon was seen when scammers started selling each other minor objects, back and forth, for nominal fees, to build up their “trusted seller” ratings. Then they would go and victimize an innocent seller or shopper – either selling them a laptop or camera that never arrived, or buying expensive jewelry with payments that turned out to be fraudulent.

“A typical game theoretic approach is to ‘be generous, be generous, be generous [and then] backstab!’” said Williams “And then make that backstab a thousand times larger than the small-asset generosity. So that’s what people do to game EBay or any system like it. They build up higher and higher trust scores, sometimes artificially, sometimes by selling lots of things at a small cost because the ratings, and the scores of whether this person is trustworthy, are based on volume.

“I’m sure that EBay has algorithms for catching people like this now, but back in the day, this was Wild West stuff.

“So the situation was that you’d run across someone who has 800 positive ratings, and you say, ‘Yes I will sell you a car,” and then they screw you for 20 grand. Whoops.

“Everyone else said they were trustworthy. Well, they were. But it was for a total of 20 bucks.”

Still need a human in the loop

Detractors fear that the increased use of algorithms and behavior modeling to catch criminals could lead to a world where fitting a profile would result in conviction for a crime the individual never committed.

This is why the tools that Ninja Metrics and other Big Data analytic companies have developed for detecting and catching online crooks still need human intervention. All the dashboards and analytics suites in the world cannot completely automate the process of maintaining a trustworthy and reliable online marketplace – in just the same way that data analysis in the real world still has to comply with civil liberties and constitutional protections.

“The metaphor I like to give whenever you do predictive analytics with Big Modeling or Big Data like this, is that you have giant stack of hay, and you’re removing 99 percent of the hay, and telling a smart person, ‘Now look for the needle,’” Williams says. “You never want to automate that final decision. You always need a human in the loop for this. But you can get rid of a lot of hay.

“We can find suspicious characters and be able to say, ‘It’s 80 percent likely that this person is this class of criminal,’ when compared to a random person off the street. And we can then extend that to catch the rest of the criminals in that group. But the last step should be, has to be, something that involves a human being.”

This is where the “Creative Data Scientist” comes in. There is an urgent, and growing, need for talented individuals who have a “foot in both worlds” — that is, someone with a data background, who can see beyond the numbers. Or an innovative artist/writer/designer, who doesn’t freak out when confronted with dense rows and columns of numbers.

Is this the first step in establishing a “Minority Report” style Department of Pre-Crime? Probably not (although if you find me shaved bald and floating in a warm swimming pool wearing a mesh leotard in a couple of years, I’ll concede that I might be wrong on this point).

But the larger point is that as crime gets more and more complex, and the vast digital infrastructure makes it easier for bad guys to pop up, do their dirty deeds, and then escape into the anonymity of cyberspace, we are going to need a new type of Digital Lawman; specifically, a Digital Detective, skilled at reading the clues left behind, and then interpolating from all that, whodunit.